No products in the cart.

Upcoming Shows

The Moving Picture Show presents

The Gold Rush

The Gold Rush is Chaplin’s greatest and most ambitious silent film; it also was the longest and most expensive comedy film produced up to that time. The film contains many of Chaplin's most celebrated comedy sequences, including the boiling and eating of his boot, the dance of the rolls, and the teetering cabin Charles Chaplin made The Gold Rush out of the most unlikely sources for comedy. The first idea came to him when he was viewing some stereoscope pictures of the 1896 Klondike gold rush, and was particularly struck by the image of an endless line of prospectors snaking up the Chilkoot Pass, the gateway to the gold fields. At the same time he happened to read a book about the Donner Party Disaster of 1846, when a party of immigrants, snowbound in the Sierra Nevada, were reduced to eating their own moccasins and the corpses of their dead comrades. Chaplin - transform these tales of privation and horror into a comedy. He decided that his familiar tramp figure should become a gold prospector, joining the mass of brave optimists to face all the hazards of cold, For the main shooting the unit worked in the Hollywood studio, where a remarkably convincing miniature mountain range was created out of timber (a quarter of a million feet, it was reported), chicken wire, burlap, plaster, salt and flour. The spectacle of this Alaskan snowscape improbably glistening under the baking Californian summer sun drew crowds of sightseers.

Watch for details of the next show

The Sentimental Bloke

Civic Theatre, 16 Macmahon Street, Hurstville, NSW 2220March 1 at 2 pm

TICKETS ADULT $31

CONCESSION $25

For enquiries and bookings

- Home : 95852408 | Mobile : 0475500001

- E-mail :stgeorgeplayers@gmail.com

- Website : themovingpictureshow.com.au

- Sentimentalbloke.eventbrite.com.au

Tickets are to be bought from our website

themovingpictureshow.com.au/tickets

or Eventbrite

goldrushcharliechaplin.eventbrite.com.au

Let's Talk

Fill in the

form and ring or email it to us

The Moving Picture Show presents

The Kid Stakes

As a celebration of the hundredth anniversary of the Country Women’s Association, we are showing The Kid Stakes, one of the real gems of Australian silent-era cinema made in 1927. Filmed in the area around Woolloomooloo, Potts Point, Centennial Park, and the Moore Park Showground. The part of Sydney where the CWA first began. All based on the Fatty Finn weekly newspaper comic strip

plus

Big Business and Liberty

Big Business features Laurel and Hardy celebrating Christmas in California and is regarded today as the greatest of all the Laurel and Hardy silent comedies. Liberty shows the boys teetering around half-built skyscrapers.

These were made just before the boys went on to achieve great success in the talkies.

Saturday, November 19, 2022 2 pm

Civic Theatre, Hurstville Entertainment Centre

Contact Us

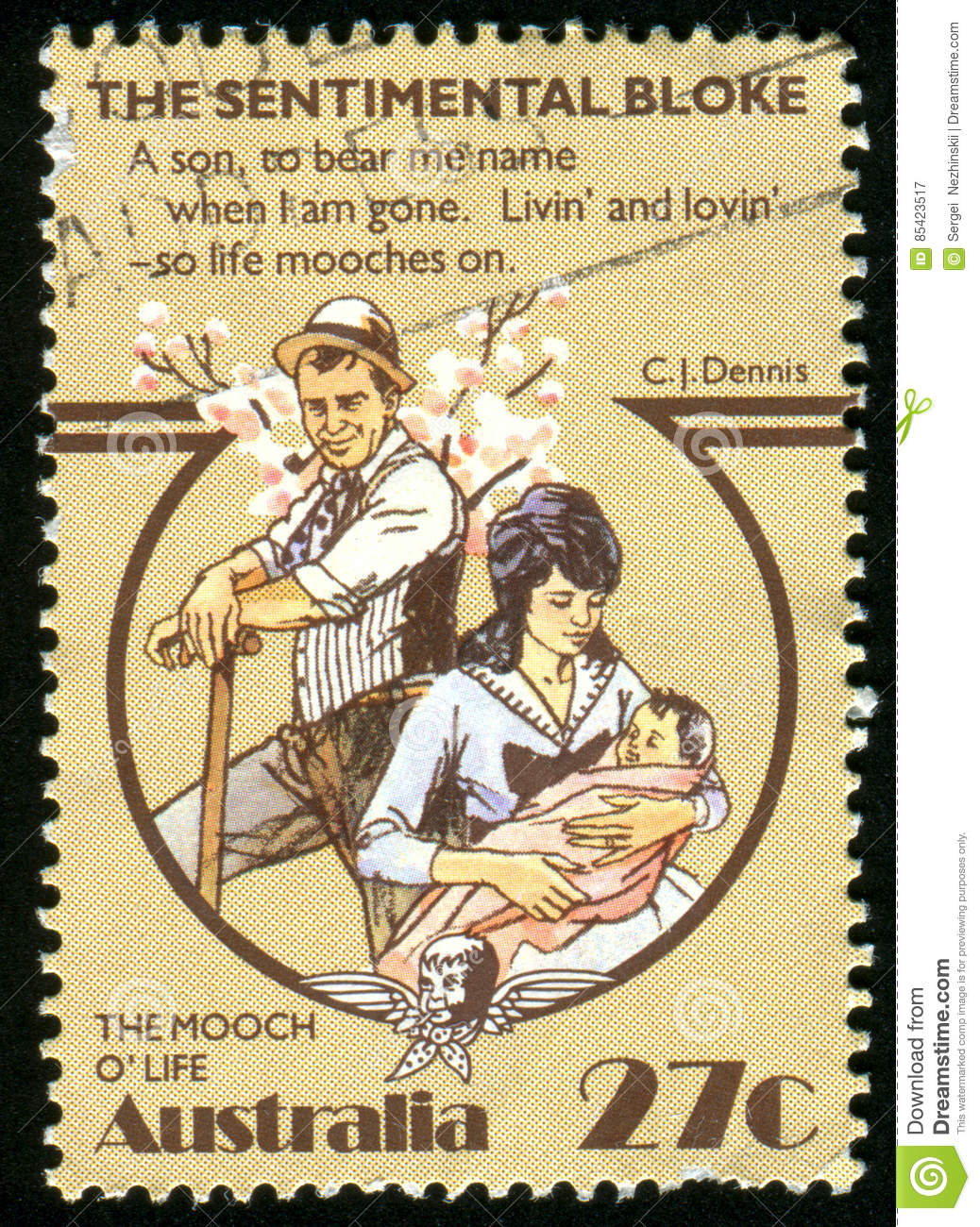

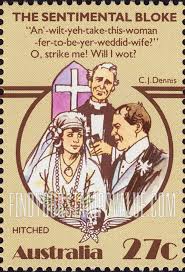

The Sentimental Bloke (1919) is an Australian silent film based on the 1915 poem The Songs of a Sentimental Bloke by C. J. Dennis. Produced and directed by Raymond Longford, it is generally considered the greatest Australian silent film, and one of the best Australian movies of all time This extraordinary production’s reputation is deserved, though the claim that it represents the peak of film-making in this country during that period is complicated by the tragic fact that the vast majority of silent Australian films have been lost. Longford made his masterpiece with long-time collaborator and fellow pioneer Lottie Lyell, who was one of Australia’s first film stars and a hugely influential figure, obscured by history but far from forgotten.

The Sentimental Bloke opened to the public in 1919 Adapted from beloved poems by C.J. Dennis, it is set in Sydney’s working-class suburbs and follows a rough but sweet larrikin, Bill (Arthur Tauchert). He is inspired by a new love interest, Doreen (Lyell), to give up drinking, gambling and brawling for a family-centric life on the street and narrow.

The actors don’t perform in the exaggerated style associated with silent pictures; there is actually much more flamboyance in the film’s dialogue than their delivery, which is presented in deeply memorable intertitles that lend a different kind of meaning to the term “visual poetry”.

Using Dennis’s prose, which was written in Australian slang, the intertitles in effect capture the protagonist talking to the audience in his, shall we say, native tongue When the protagonist first sees Doreen he is smitten: I seen ‘er in the market first uv all,Inspectin’ brums at Steeny Isaacs’ stall. Having mustered the courage to make small talk, Bill is disappointed by Doreen’s unenthusiastic response (she’s far from a pushover), but later convinces her to date him. Their nights on the town include a trip to the theatre to see a Shakespeare play “about a barmy goat called Romeo”, and a trip to the beach. He reflects on their tender moment on the sand: ‘Oldin’ in me own ‘Er little ‘and,

An’ ‘ow she blushed! O, strike! it was divine

The way she raised ‘er shinin’ eyes to mine

Some of the language has dated, of course – including Bill’s fondness for describing the opposite sex as “tarts”, and one use of a racial slur to describe a time of the day (taken from Dennis’s poems). But the story is enormously warm-hearted and remarkable in its timelessness. And with its at-first-blush tough guy protagonist who turns out to be needy, sensitive and openly breaks down in tears, it explores Australian masculinity in a more interesting, meaningful way than the majority of films released today.